The nation’s Social Security program was designed with special concern for the least fortunate Americans, to keep them from sinking into poverty when they became too old to work.

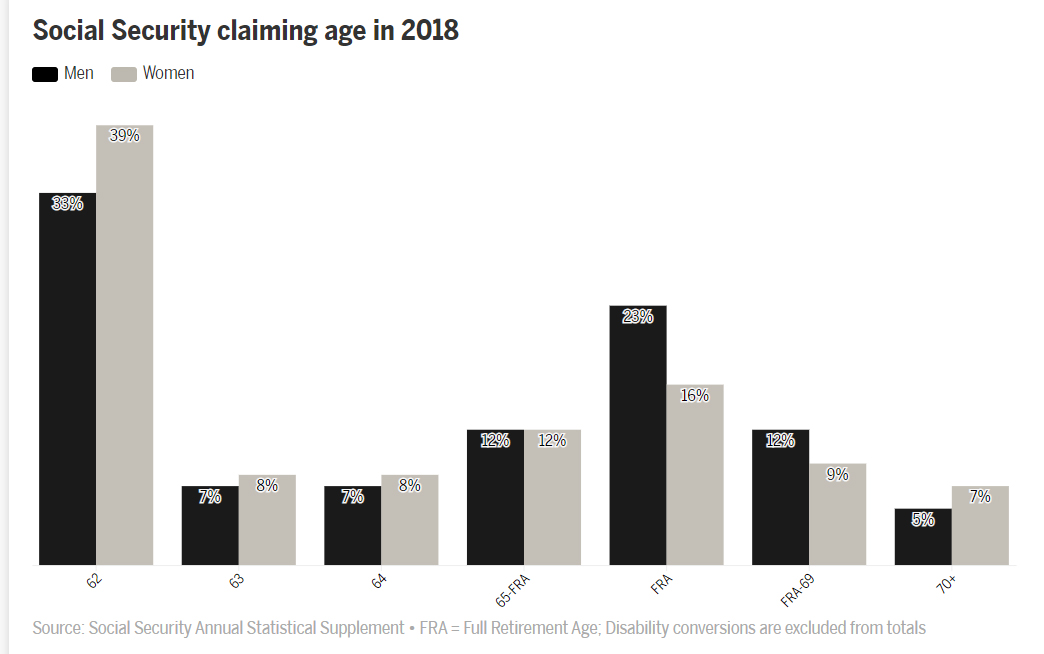

But recent demographic changes have tilted the system against lower earners who claim Social Security benefits early, even as they’ve rewarded higher earners who claim benefits later, according to a Boston College report.

That report, from the college’s Center for Retirement Research, details how longer life spans have scrambled the decades-old calculations that determine the payouts Americans receive at full retirement age, and the adjustments for claiming Social Security benefits early or later.

Higher earners who can afford to delay benefits are living significantly longer — and reaping benefits longer — than poorer people who need the money right away.

“Lower earners were supposed to gain more from Social Security,” said Anqi Chen, coauthor of the report. “But those who can’t wait to collect at their full retirement age are now getting penalized.”

Many of those who begin collecting later are often seniors in good health working at white-collar jobs deep into their 60s, and they can look forward to larger Social Security checks for decades.

It’s only the latest evidence of what many see as a swing away from Social Security’s foundational promise to help low- and middle-income Americans in retirement.

“The program’s become less progressive,” said a retired Tufts Health Plan president, Jim Roosevelt. He is also a former associate commissioner for retirement policy at the Social Security Administration and a grandson of the late president who ushered in Social Security in the 1930s. “It doesn’t take care of the people at the lower- and middle-income levels as well as it was intended do, and it needs to be updated,” he said.

He pointed to other factors, such as a cap on income subject to Social Security withdrawals, that also benefit the highest earners.

Tilts to favor higher earners who delay claiming

Employees who earn more than $132,900 in 2019 — about 6.2 percent of US workers — make no Social Security contributions on additional earnings. While that cap excluded only 10 percent of earned income when it was established in the 1980s, increasing income inequality has boosted the share that’s excluded to 18 percent.

That has deprived the system of money it needs to survive at a time when historically low interest rates have further weakened the Social Security trust fund, which is invested in rate-sensitive US Treasury bonds.

CONTINUE READING AT BostonGlobe.com