From MedicalXpress.com —

In the United States, 5 percent to 10 percent of adults 65 and older are victims of elder abuse and mistreatment, public health experts say. Yet only one in 24 cases is ever identified. One of the barriers is a basic misunderstanding of just what constitutes mistreatment, which prevents many victims from reporting abuse.

A digital screening tool developed by Yale researchers aims to help overcome this challenge.

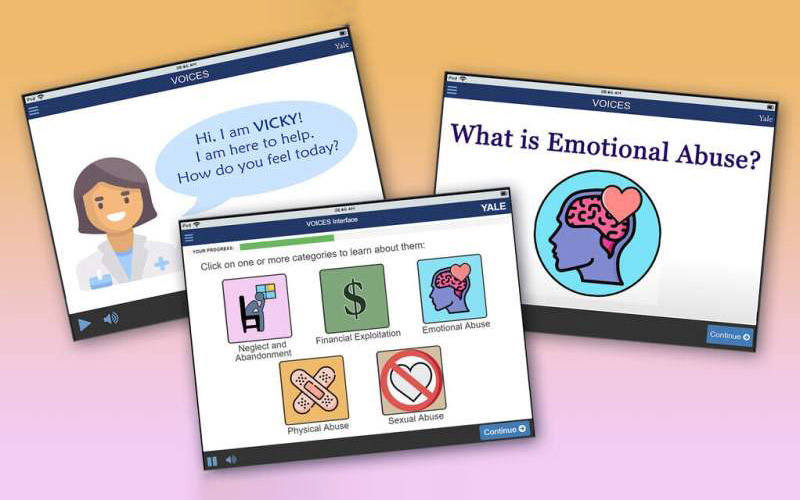

VOICES, or Virtual cOaching in making Informed Choices on Elder Mistreatment Self-Disclosure, created for use on tablet devices, combines multimedia presentations and virtually guided interviews to educate and empower older adults.

Health care providers can use the VOICES tool to reveal cases of abuse in which evidence is not otherwise apparent. The tool walks older adults through a series of video modules. One describes what elder abuse is, revealing how abusive situations tend to escalate and suggesting the kinds of help available. Other modules detail the different kinds of abuse, including emotional abuse or neglect.

And it encourages users to reflect on their own experiences with questions like, “Do you feel you have been mistreated in any way in last 12 months?”

If the user identifies as a victim, a final module urges them to seek help.

“The techniques we’re using in VOICES haven’t been used before in abuse situations,” said Fuad Abujarad, associate professor of emergency medicine at Yale and principal investigator of the project. “This tool is about more than just screening. It’s also about education and empowerment. And, so far, our research has shown that this three-pronged approach could make a difference.”

Numerous factors contribute to the underreporting of elder abuse. These include a lack of appropriate screening mechanisms and, given the sensitivity of the issue, hesitancy to approach the topic. Older adults may also choose not to report mistreatment for fear that they might get a caregiver in trouble, be moved to a nursing home, or lose their autonomy.

To date, efforts to improve the identification of abuse have focused on educating health care professionals and creating tools for them to administer. VOICES takes a new approach by bringing older adults into the process and empowering them to advocate for themselves.

The project, which was launched in 2018 with support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has continued to expand in scope. Initially researchers envisioned that the technology would be used in emergency rooms, a critical point of care for many older adults and the first point of care for many. But they are now testing VOICES in primary care settings, too. They are also adapting it for use among older adults with disabilities and cognitive impairments.

Creating a tool for use by such a broad range of users—and for such a complex and sensitive challenge—requires all sorts of expertise. As VOICES has grown, so too has its interdisciplinary team. Researchers and practitioners in emergency medicine, geriatrics, biostatistics, psychology, psychiatry, and internal medicine represent just a few of the fields involved in the project.

Kellen McDonald is a student in Yale’s joint degree program at Yale School of Nursing and Yale School of Public Health (YSPH). For the past year, she has helped recruit study participants and worked with them.

“When I was applying to nursing school, all of my essays were about interdisciplinary solutions to complex health care issues,” she said. “The VOICES project is the type of work I said I wanted to do, and now I’m doing it. It feels like I’ve come full circle.”

At YSPH, she is focused on social and behavioral sciences. “To be able to combine what I’ve learned in my classes with what I’m learning in this project, and then see it have an impact on patients, is really powerful.”

The project has also included collaborators from outside Yale, including several co-investigators at universities across the country as well as partners closer to home.

Carol Hunihan is a 76-year-old Woodbridge resident who tested VOICES and offered feedback. Hunihan, along with other volunteer participants, used the tool and provided suggestions on the wording used in communicating with users, font size, and other aspects of the VOICES design. Specifically, she was asked to assess the tool from the point of view of someone who might encounter it in an emergency room.

“This is an important tool. It’s crucial,” she said. “I think VOICES will get more people the help they need.”

The VOICES team is now developing a Spanish-language version. For this part of the project, Abujarad recruited Maripaz Garcia, a senior lecturer in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, who has synthesized two independently produced translations into one. Her team has since recruited another set of translators to conduct a reverse translation, from Spanish back to English, to make sure nothing was lost during the initial translation process. Their multi-step approach was published Feb. 17 in the International Journal of Translation and Interpretation Studies.

Next, Spanish-speaking older adults will test the tool and provide feedback, and then the research team will conduct pilot studies of the Spanish version.

Garcia adds that it is not only the language that’s being translated; the Spanish version incorporates cultural adaptation, too. “Some questions may not be appropriate for different cultures, so language has to be adjusted to account for that,” she said. “As the Spanish version of VOICES goes through this translation and testing process, we’ll continue to make these adaptations to ensure the tool is as effective as possible.”

“This can’t be just a straight translation,” added Abujarad. “We’re touching people’s hearts and, unfortunately, this topic can be considered taboo. To translate a tool like this and have it be accepted by the cultures that speak that language, we have to do cultural adaptation.”

The VOICES team will continue to expand. Abujarad is currently looking for community-based settings outside of academic clinics to test VOICES. He said there’s interest in other parts of the country; it’s likely parallel trials will run in two or three locations across the United States.

“This technique is working. We’re seeing signs of success,” said Abujarad. “We don’t want to wait years and years before we get this in the hands of patients.”